Johnson, Clifton, 1865-1940, “A quiet afternoon,” Digital Amherst, accessed September 7, 2022, https://www.digitalamherst.org/items/show/2810.

Johnson, Clifton, 1865-1940, “A quiet afternoon,” Digital Amherst, accessed September 7, 2022, https://www.digitalamherst.org/items/show/2810.

In the aftermath of the Revolutionary War, early Americans in Hampshire County and beyond renewed a relationship with sheep with more intention than ever before. The boycotting of British goods had forged a link between domestic production of textiles and newfound American identity. This motivated many to redouble their efforts to strengthen domestic textile manufacturing as a matter of national interest.1 But there was also money to be made. British woolen manufacturing technology, zealously guarded for many years, finally started to trickle across the Atlantic around 1790 thanks to intentional international espionage, smuggled machinery, and skilled immigrant labor.2 American policies like the Non-Importation Act of 1806 and the Embargo Act of 1807, intended to influence global conflicts with Britain and France, also placed additional pressure on the nascent domestic textile industries because imported textiles were banned. Against this global backdrop, early Americans were motivated to establish mechanized woolen industries in their new nation and increase their supply of wool.

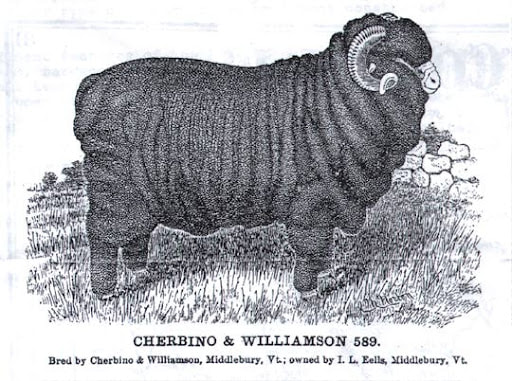

Late nineteenth-century advertisement for Merino sheep in Middlebury, VT, illustrating their wrinkly, wooly appearances.

Late nineteenth-century advertisement for Merino sheep in Middlebury, VT, illustrating their wrinkly, wooly appearances.

The First Merino Craze

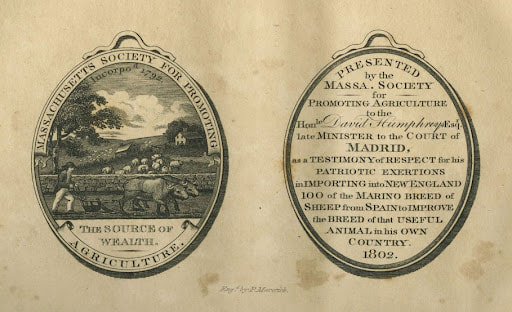

Sheep fever reached its peak at the beginning of the nineteenth century when many aspiring American sheep farmers and textile tycoons pinned their hopes on Merino sheep, a Spanish breed of sheep valued for its thick, fine wool. Compared to other sheep breeds in early America like Wiltshires and Romneys, Merinos had denser fleeces that could produce more wool per sheep, giving them distinctive wrinkly appearances. Pure merinos were highly prized, but strategic crossbreeding with Merinos could also produce other sheep with woollier fleeces. Robert Livingston, the former Chancellor of New York, published the book Essay on Sheep in 1809 and highly praised the Merino sheep as bearing “the finest fleeces of any known in Europe,” which greatly encouraged further Merino import.3Livingston’s own flock of imported merino sheep, along with Colonel David Humpreys’ merino flock in Connecticut, were the main source for Merinos entering sheep flocks in Western Massachusetts.4 Humphrey’s merino sheep flock was deemed so influential that the Massachusetts Society for Promoting Agriculture awarded him a gold medal. Wealthy American businessmen spent upwards of $1500 per Merino ram to enter the market, and thousands of acres in Vermont, New Hampshire, New York, and Massachusetts were cleared to hold growing Merino flocks in the 1810s and 1820s.

Sheep fever reached its peak at the beginning of the nineteenth century when many aspiring American sheep farmers and textile tycoons pinned their hopes on Merino sheep, a Spanish breed of sheep valued for its thick, fine wool. Compared to other sheep breeds in early America like Wiltshires and Romneys, Merinos had denser fleeces that could produce more wool per sheep, giving them distinctive wrinkly appearances. Pure merinos were highly prized, but strategic crossbreeding with Merinos could also produce other sheep with woollier fleeces. Robert Livingston, the former Chancellor of New York, published the book Essay on Sheep in 1809 and highly praised the Merino sheep as bearing “the finest fleeces of any known in Europe,” which greatly encouraged further Merino import.3Livingston’s own flock of imported merino sheep, along with Colonel David Humpreys’ merino flock in Connecticut, were the main source for Merinos entering sheep flocks in Western Massachusetts.4 Humphrey’s merino sheep flock was deemed so influential that the Massachusetts Society for Promoting Agriculture awarded him a gold medal. Wealthy American businessmen spent upwards of $1500 per Merino ram to enter the market, and thousands of acres in Vermont, New Hampshire, New York, and Massachusetts were cleared to hold growing Merino flocks in the 1810s and 1820s.

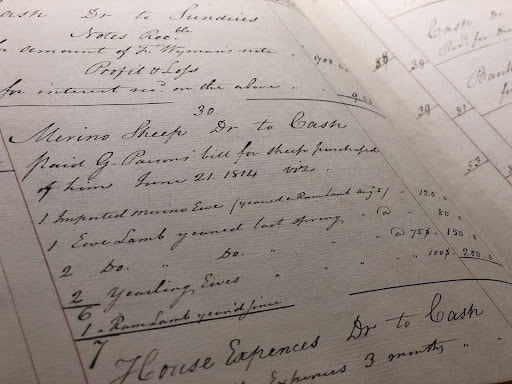

Waste Book A (1800-1825), September 2, 1814, Phelps and Rand Collection, Baker Library, Harvard University.

Waste Book A (1800-1825), September 2, 1814, Phelps and Rand Collection, Baker Library, Harvard University.

In Western Massachusetts, residents were also swept up in sheep expansion. In Franklin, Hampden, and Hampshire Counties, the area of meadow land increased from 79,152 to 146,393 acres between 1801 and 1845.5 Farmers in Hampshire County such as Hadley’s Charles P. Phelps purchased Merino sheep both imported and domestically raised and noted this purchase in his account books. Towns like Northampton, Belchertown, Cummington and Hatfield all became agricultural strongholds in the county for sheep production.6Multiple agricultural organizations also formed, addressing all manner of farming-relationed issues which also included sheep. The Hampshire,

Early nineteenth-century carding machine in operation at Old Sturbridge Village in Sturbridge, MA. www.osv.org

Early nineteenth-century carding machine in operation at Old Sturbridge Village in Sturbridge, MA. www.osv.org

Franklin and Hampden Agricultural Society was founded in 1818, and similar organizations more locally focused also sprang up, like the Farmer’s Club of Sunderland and the Franklin Harvest Club in Greenfield.7 These organizations stayed apprised of current agricultural practices and local numbers of sheep in their locations, sharing this information internally and publicly. Sheep farming best practices populated the meeting minutes of the North Hadley Farmer’s Club in 1839, while in 1870 the Franklin Harvest Club documented sheep numbers in Hatfield between 5-6,000.8

Wooly Mechanization

Although infused with an influx of domestic wool, mechanized woolen textile production in Massachusetts did not immediately begin under one roof, but rather in various decentralized stages across the landscape. In addition to raising sheep for their wool, Hampshire County residents ran carding mills, small water-powered mills that mechanized the process of combing woolen fibers into rolls that could then be spun. The process of carding wool, initially a time-consuming process done exclusively by hand, had transitioned to hand cards, wooden boards with handles fastened to rows of wire bristles, by the early modern period. Carding mills took this technological evolution a step further and implemented a wire bristled cylinder that carded as it turned.9

Wooly Mechanization

Although infused with an influx of domestic wool, mechanized woolen textile production in Massachusetts did not immediately begin under one roof, but rather in various decentralized stages across the landscape. In addition to raising sheep for their wool, Hampshire County residents ran carding mills, small water-powered mills that mechanized the process of combing woolen fibers into rolls that could then be spun. The process of carding wool, initially a time-consuming process done exclusively by hand, had transitioned to hand cards, wooden boards with handles fastened to rows of wire bristles, by the early modern period. Carding mills took this technological evolution a step further and implemented a wire bristled cylinder that carded as it turned.9

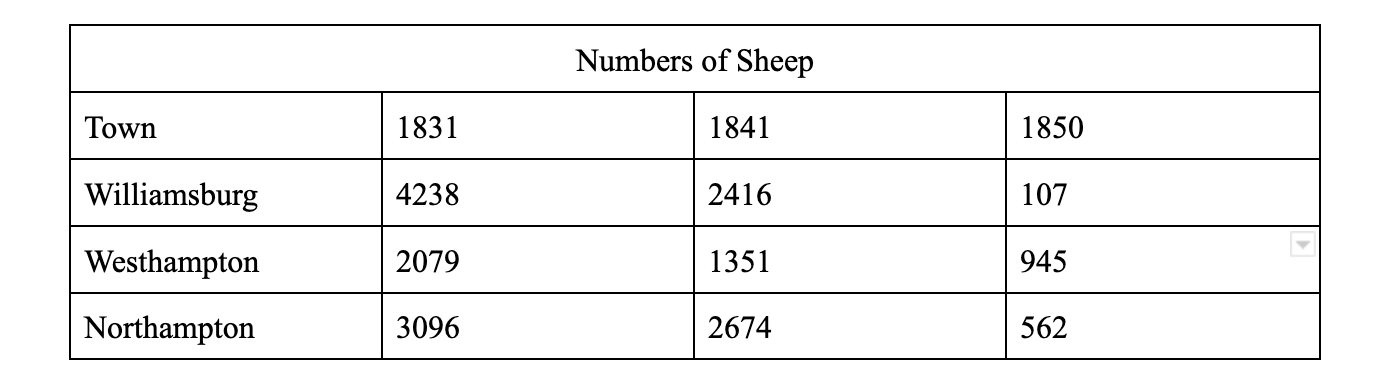

Data from Christopher Clark, Roots of Rural Capitalism (Ithaca: Cornell, 1992), 268.

Data from Christopher Clark, Roots of Rural Capitalism (Ithaca: Cornell, 1992), 268.

In time, modifications to the carding mill added an additional step of rolling the carded fiber into a continuous fluffy length known as roving. British immigrants John and Arthur Scholfield recreated carding machines in 1795 as a key part of operations at the Newburyport Woolen Factory, but eventually established their own business in 1803 making and selling carding machines in the Pittsfield area that would become the core of mills in Western Massachusetts.10 Alongside available water power, multiple carding mills sprang up in North Amherst, Hadley, and North Hadley to comb wool for local residents. Today, these carding mills no longer dot the landscape, but a surviving Scholfield carding machine is still in operation at Old Sturbridge Village. More broadly, woolen mills that encompassed multiple stages of woolen cloth production exponentially grew. In 1813, Massachusetts contained five woolen mills which required 35,000 pounds of wool annually, and by 1837 there were 192 woolen mills which consumed 10,858,988 pounds of wool. 11

From Sheep for Wool to Sheep for Meat

New England sheep farming for wool and woolen manufactories experienced several tumultuous decades influenced by global politics and financial panics, but both reached a peak just before 1840. In 1870, 112,047 sheep were documented in the entire state of Massachusetts.12 Sheep farming began to shift westwards away from the east coast and early American farmers diversified their practices away from solely sheep farming to take advantage of emerging markets like dairy and grain.13 New sheep breed crosses were also introduced and exclusively raised for their meat, rather than both their wool and their meat. Mechanized woolen production, however, continued. Between 1837 and 1845, the number of sheep in the Connecticut River Valley decreased by four thousand sheep even as there was a fifty percent increase in Massachusetts factories’ wool consumption.14

From Sheep for Wool to Sheep for Meat

New England sheep farming for wool and woolen manufactories experienced several tumultuous decades influenced by global politics and financial panics, but both reached a peak just before 1840. In 1870, 112,047 sheep were documented in the entire state of Massachusetts.12 Sheep farming began to shift westwards away from the east coast and early American farmers diversified their practices away from solely sheep farming to take advantage of emerging markets like dairy and grain.13 New sheep breed crosses were also introduced and exclusively raised for their meat, rather than both their wool and their meat. Mechanized woolen production, however, continued. Between 1837 and 1845, the number of sheep in the Connecticut River Valley decreased by four thousand sheep even as there was a fifty percent increase in Massachusetts factories’ wool consumption.14

The Civil War inspired a surge of interest due to the high demand for wool that could clothe soldiers in the military, but this brief spike in demand was followed with sharp decline after the war’s conclusion. In Hampshire County, these national fluctuations changed the local landscape of farming. Post-war agricultural censuses show farmers in towns like Hatfield,Hadley, and Belchertown continuing to raise smaller flocks of sheep for wool, but more often farmers raised and sold off much larger numbers of sheep for meat, known as mutton, within the same year. For example, Franklin H. Bryant of Chesterfield, who helped found the Chesterfield Grange, maintained a flock of 150 sheep and had 108 fleeces after shearing, while Oscar Belden of Hatfield, whose farm would eventually house one of the largest sheep flocks on the east coast by the early twentieth-century, turned over upwards of 400 sheep each for meat in the 1880 agricultural census.15This turn to raising sheep for meat was in part due to a rise in popularity of “hothouse lambs” which were born and raised out of traditional lambing seasons and were sold in very early spring, as well as the development of centralized slaughterhouses, bringing mutton into more affordable consumption for a period.16

Numbers for sheep to be fatted and sold on Hampshire County farms reached the thousands, and in some instances, larger midwestern farms were the source. In 1870, Thadeus Smith traveled to Albany to procure 1800 Michigan sheep for fattening in the Hadley area.17 These sheep could have traveled from the midwest down to Albany on one of the major transportation revolutions of the nineteenth century - the railroad. Hampshire County farmers used rail in the nineteenth century to send their sheep down to major urban centers like New York, which is still a destination for sheep raised in this area today. Alongside massive technological advancement, larger distances between sheep farms and markets, and transitioning preferences for mutton consumption, Hampshire County farmers adapted to include sheep in their growing constellation of agricultural enterprises.

Numbers for sheep to be fatted and sold on Hampshire County farms reached the thousands, and in some instances, larger midwestern farms were the source. In 1870, Thadeus Smith traveled to Albany to procure 1800 Michigan sheep for fattening in the Hadley area.17 These sheep could have traveled from the midwest down to Albany on one of the major transportation revolutions of the nineteenth century - the railroad. Hampshire County farmers used rail in the nineteenth century to send their sheep down to major urban centers like New York, which is still a destination for sheep raised in this area today. Alongside massive technological advancement, larger distances between sheep farms and markets, and transitioning preferences for mutton consumption, Hampshire County farmers adapted to include sheep in their growing constellation of agricultural enterprises.

1 Peggy Hart, Wool: Unraveling an American Story of Artisans and Innovation (Atglen: Schiffer Publishing, 2017), 50-55.

2 David Jeremy, TransAtlantic Industrial Revolution: Diffusion of Textile Technologies Between Britain and America, 1790-1830s (Hoboken: Blackwell/MIT, 1981), 20.

3 Robert R. Livingston, Essay on Sheep: Their Varieties - Account of the Merinoes of Spain, France &c. Reflections on the Best Method of Treating Them, and Raising a Flock in the United States : Together with Miscellaneous Remarks on Sheep, and Woollen Manufactures, Third edition (Concord: Daniel Cooledge, 1813), 31.

4L.G. Connor, “A Brief History of the Sheep Industry in the United States,” Agricultural History Society Papers , 1921, Vol. 1 (1921), 130.

5 Martin P. Plantinga, “Agricultural land utilization in the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts” (B.S. Thesis, Massachusetts State College, 1933), 41.

6 See Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC), “Historical and Archaeological Resources of the Connecticut River Valley,” https://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpdf/regionalreports/ctvalley.pdf, 93.

Wells History of Hatfield p. 219 describes fattening of sheep around 1815, and says the largest (farms of Elijah Bardwell and Reuban Belding) had as many as 1000, though others had 100-500.

7http://americancenturies.mass.edu/collection/itempage.jsp?itemid=15474&img=0&level=advanced&transcription=0

8Hampshire Gazette, February 1, 1870. North Hadley Farmer’s Club meeting log Monday Eve January 3 1839 SCUA

9 Grace L Rogers, “The Scholfield Wool-Carding Machines” United States National Museum Bulletin 218: Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology Paper 1 (Washington: Smithsonian,1959)

https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/21285/USNMB-218_1_1959_413.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

10 Grace L Rogers, “The Scholfield Wool-Carding Machines” United States National Museum Bulletin 218: Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology Paper 1 (Washington: Smithsonian,1959),

https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/21285/USNMB-218_1_1959_413.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

11 Martin P. Plantinga, “Agricultural land utilization in the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts” (B.S. Thesis, Massachusetts State College, 1933), 42-43.

12Hampshire Gazette, March 8, 1870.

13 L.G. Connor, “A Brief History of the Sheep Industry in the United States,” Agricultural History Society Papers , 1921, Vol. 1 (1921), 113.

14 Martin P. Plantinga, “Agricultural land utilization in the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts” (B.S. Thesis, Massachusetts State College, 1933), 44.

15 Although the Beldens no longer raise sheep, their farm is still active in Hatfield today. See Ruth A. Baker, History and Genealogy of the Families of Chesterfield, Mass (Northampton: Gazette Printing Co., 1962), Hatfield Reconnaissance Report: Connecticut Reconnaissance Survey, Massachusetts Heritage Inventory Program, 2009). https://www.mass.gov/doc/hatfield/download, and U.S., Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules, 1850-1880 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

16 L.G. Connor, “A Brief History of the Sheep Industry in the United States,” Agricultural History Society Papers , 1921, Vol. 1 (1921), 150.

17 Hampshire Gazette, December 6, 1870.

2 David Jeremy, TransAtlantic Industrial Revolution: Diffusion of Textile Technologies Between Britain and America, 1790-1830s (Hoboken: Blackwell/MIT, 1981), 20.

3 Robert R. Livingston, Essay on Sheep: Their Varieties - Account of the Merinoes of Spain, France &c. Reflections on the Best Method of Treating Them, and Raising a Flock in the United States : Together with Miscellaneous Remarks on Sheep, and Woollen Manufactures, Third edition (Concord: Daniel Cooledge, 1813), 31.

4L.G. Connor, “A Brief History of the Sheep Industry in the United States,” Agricultural History Society Papers , 1921, Vol. 1 (1921), 130.

5 Martin P. Plantinga, “Agricultural land utilization in the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts” (B.S. Thesis, Massachusetts State College, 1933), 41.

6 See Massachusetts Historical Commission (MHC), “Historical and Archaeological Resources of the Connecticut River Valley,” https://www.sec.state.ma.us/mhc/mhcpdf/regionalreports/ctvalley.pdf, 93.

Wells History of Hatfield p. 219 describes fattening of sheep around 1815, and says the largest (farms of Elijah Bardwell and Reuban Belding) had as many as 1000, though others had 100-500.

7http://americancenturies.mass.edu/collection/itempage.jsp?itemid=15474&img=0&level=advanced&transcription=0

8Hampshire Gazette, February 1, 1870. North Hadley Farmer’s Club meeting log Monday Eve January 3 1839 SCUA

9 Grace L Rogers, “The Scholfield Wool-Carding Machines” United States National Museum Bulletin 218: Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology Paper 1 (Washington: Smithsonian,1959)

https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/21285/USNMB-218_1_1959_413.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

10 Grace L Rogers, “The Scholfield Wool-Carding Machines” United States National Museum Bulletin 218: Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology Paper 1 (Washington: Smithsonian,1959),

https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/21285/USNMB-218_1_1959_413.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

11 Martin P. Plantinga, “Agricultural land utilization in the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts” (B.S. Thesis, Massachusetts State College, 1933), 42-43.

12Hampshire Gazette, March 8, 1870.

13 L.G. Connor, “A Brief History of the Sheep Industry in the United States,” Agricultural History Society Papers , 1921, Vol. 1 (1921), 113.

14 Martin P. Plantinga, “Agricultural land utilization in the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts” (B.S. Thesis, Massachusetts State College, 1933), 44.

15 Although the Beldens no longer raise sheep, their farm is still active in Hatfield today. See Ruth A. Baker, History and Genealogy of the Families of Chesterfield, Mass (Northampton: Gazette Printing Co., 1962), Hatfield Reconnaissance Report: Connecticut Reconnaissance Survey, Massachusetts Heritage Inventory Program, 2009). https://www.mass.gov/doc/hatfield/download, and U.S., Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules, 1850-1880 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

16 L.G. Connor, “A Brief History of the Sheep Industry in the United States,” Agricultural History Society Papers , 1921, Vol. 1 (1921), 150.

17 Hampshire Gazette, December 6, 1870.

Proudly powered by Weebly