Stone walls, usually now surrounded by woods, are evidence of onetime sheep pastures (photo: Marla Miller)

Stone walls, usually now surrounded by woods, are evidence of onetime sheep pastures (photo: Marla Miller)

Objects, buildings, and landscapes related to the history of sheep in Hampshire County are all around us. For instance, in addition to agricultural landscapes, buildings and outbuildings associated with sheep cultivation, it is easy to find–in fields and forests–stone walls that are evidence of onetime sheep pastures. Their construction documents both the boom in interest in sheep cultivation in the 19-teens, and the eventual abandonment of that practice around 1840. These walls in the woods tell a very specific story about a moment in time when interest in sheep cultivation was exceptionally high among Massachusetts farmers.

Also present on the land are objects that, while also in stone, are of a very different sort: gravestones that tap the iconography of sheep to cue ideas about childhood and innocence, as cemeteries contain headstones (particularly when the deceased is associated with the Catholic faith, and died during the Victorian era, when childhood was viewed with much sentimentality) reflecting understandings of Christ as a shepherd, and children as lambs of God.

Also present on the land are objects that, while also in stone, are of a very different sort: gravestones that tap the iconography of sheep to cue ideas about childhood and innocence, as cemeteries contain headstones (particularly when the deceased is associated with the Catholic faith, and died during the Victorian era, when childhood was viewed with much sentimentality) reflecting understandings of Christ as a shepherd, and children as lambs of God.

19th-century gravestones, like this one in Amherst, used iconography of sheep to signal innocence and childhood (photo: Marla Miller)

19th-century gravestones, like this one in Amherst, used iconography of sheep to signal innocence and childhood (photo: Marla Miller)

The material culture of sheep documents the many roles sheep have played in American culture and society, in histories agricultural and economic, but also social, cultural, and aesthetic. Museums and historic sites around Hampshire County and beyond preserve the material culture of sheep in society and culture. Look around, and see what you can find!

Wool wheel, Porter-Phelps-Huntington Museum (photo: Porter Phelps Huntington Foundation)

Wool wheel, Porter-Phelps-Huntington Museum (photo: Porter Phelps Huntington Foundation)

The Porter-Phelps-Huntington House (Hadley)

Wool Wheels

Spinning wheels were ubiquitous in early America, necessary to process fibers, converting them to threads that were suitable then for weaving and other means of creating textiles, and today they are found throughout many museum collections. Large wheels (often called “great wheels”) designed to spin wool sat alongside smaller versions more appropriate for flax, which produced linen. A household’s production of wool did not necessarily imply its on-site conversion into yarn: in Deerfield, only half of the households that possessed sheep also owned wool-spinning wheels, suggesting that at least some sheep-growers found others in the community to do their spinning.1 By the era of the American Revolution, fully three out of every four households in Hampshire County owned a spinning wheel for either flax or wool, if not both.2

This example, from Hadley, has the initials of its owner, Whiting Elizabeth Phelps Huntington, scratched into it. Wheels of very different sizes that in turn demanded different spaces within the home; unlike flax wheels, which were much smaller, a wool wheel might reach 36” in diameter, on a base just as long. The user turned the wheel with one hand while drawing out the thread with another, walking backward and forward as the yarn lengthened and then wound on the spindle.3 Spinning wool, then, demanded settings that were often different than spinning flax, a more compact process that allowed the user to remain seated at a treadle. At Elizabeth Huntington’s home, known as Forty Acres, flax could be spun in a kitchen, a room large enough to harbor a wheel alongside all the many other tools active there, but the wool was spun in the corn house, where spinners could move more appropriately. Indeed, spinning six skeins of yarn on the great or so-called “walking” wheel could require the spinner to pace off what was the equivalent of some twenty miles, all within the walls of her own home.4 “Dancing is vapid by comparison,” Phelps’ grandson would later write.5

Wool wheels–often together with other tools associated with fiber preparation–can also be found in the collections across the area, including those of Historic Deerfield, the Hadley Farm Museum, and Historic Northampton.

Wool Wheels

Spinning wheels were ubiquitous in early America, necessary to process fibers, converting them to threads that were suitable then for weaving and other means of creating textiles, and today they are found throughout many museum collections. Large wheels (often called “great wheels”) designed to spin wool sat alongside smaller versions more appropriate for flax, which produced linen. A household’s production of wool did not necessarily imply its on-site conversion into yarn: in Deerfield, only half of the households that possessed sheep also owned wool-spinning wheels, suggesting that at least some sheep-growers found others in the community to do their spinning.1 By the era of the American Revolution, fully three out of every four households in Hampshire County owned a spinning wheel for either flax or wool, if not both.2

This example, from Hadley, has the initials of its owner, Whiting Elizabeth Phelps Huntington, scratched into it. Wheels of very different sizes that in turn demanded different spaces within the home; unlike flax wheels, which were much smaller, a wool wheel might reach 36” in diameter, on a base just as long. The user turned the wheel with one hand while drawing out the thread with another, walking backward and forward as the yarn lengthened and then wound on the spindle.3 Spinning wool, then, demanded settings that were often different than spinning flax, a more compact process that allowed the user to remain seated at a treadle. At Elizabeth Huntington’s home, known as Forty Acres, flax could be spun in a kitchen, a room large enough to harbor a wheel alongside all the many other tools active there, but the wool was spun in the corn house, where spinners could move more appropriately. Indeed, spinning six skeins of yarn on the great or so-called “walking” wheel could require the spinner to pace off what was the equivalent of some twenty miles, all within the walls of her own home.4 “Dancing is vapid by comparison,” Phelps’ grandson would later write.5

Wool wheels–often together with other tools associated with fiber preparation–can also be found in the collections across the area, including those of Historic Deerfield, the Hadley Farm Museum, and Historic Northampton.

Shears, Hadley Farm Museum (photo: Emily Whitted)

Shears, Hadley Farm Museum (photo: Emily Whitted)

The Hadley Farm Museum (Hadley)

In the 1920s, Hadley and Springfield bookseller Henry R. Johnson and his brother, author and artist Clifton Johnson, assembled a large collection of agricultural implements. While others in the region became interested in collecting examples of early American decorative arts, the Johnsons “began their collecting at the back door.” Amid their large collection of tools associated with farming, woodworking, textile production, and other activities, they preserved artifacts

associated with sheep and wool production, from sheep shears to a sizable collection of wool cards. Related artifacts in the collection include looms, quilt frames, and other objects associated with the production and use of wool fabrics.

Wool Cards

Wool cards played an important role in the preparation of fibers for spinning. Wooden paddles with handles mounted with bent wire teeth, the cards were important tools in cloth making, allowing people, through a combing motion, to align wool fibers in preparation for spinning. The collections of the Hadley Farm Museum contain a set of wool cards that together help tell the story of wool production in Hampshire County and elsewhere. In the late eighteenth century, card production was mechanized, and objects in the collection help tell that story. One pair is marked as the product of Pliny Earle (1762-1832), a Quaker manufacturer from Leicester, Mass, who began making wool cards for Samuel Slater’s Rhode Island enterprise. Earle invented a machine for pricking "twilled" cards, a system in general use until Amos Whittemore introduced a machine that both pricked the leather and set the teeth. In 1797 Whittemore filed a patent for a machine that held, cut, and pierced a piece of leather; it drew wire from a reel which was then cut, bent, and fastened to the leather. Whittemore (b. 1759) established a wool card manufactory in Boston in 1788. The enterprise employed 900 people and produced more than 60,000 cards each year.

Wool Shears

At least once a year, sheep are shorn of their wooly fleeces using shears. While today much of the world uses shears powered by electricity, hand shears like this pair at the Hadley Farm Museum were in use for hundreds of years. Before it became a collection object, this pair would have had extremely sharp edges stored inside a leather sheath when not in use to aid the sheep shearer in a clean and efficient cut. The blades of these shears are marked with a maker’s mark KG Co encircled by a crown. Sheep shearing today can still be backbreaking work, but hand shearing was almost twice as time consuming as mechanized shearing, depending on the direction shearers took when shearing (the English method, for example, hand sheared sheep from their necks to their tails, while the Australian method went from their flanks to their heads).6The first mechanized sheep shearing was invented in the late nineteenth century, so shears like this may seem like an antiquated form of early sheep shearing technology today. But this pair is actually from the twentieth century, serving as a reminder that despite technological innovation, handwork often continued. Today, sheep shearing is usually done by a small number of trained professionals who cover regions of farmland and serve thousands of sheep during the year.

MAC Weathervane in the collection of the Hadley Farm Museum. Public Domain.

MAC Weathervane in the collection of the Hadley Farm Museum. Public Domain.

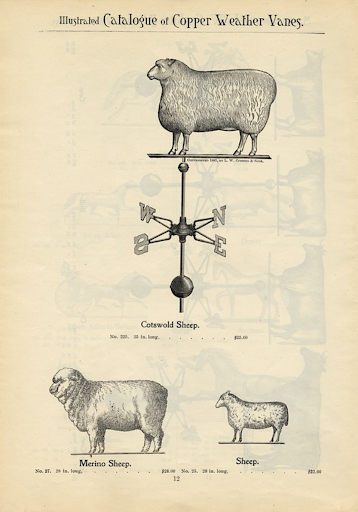

Weathervanes

The Hadley Farm Museum holds a weathervane in its collection with the initials “MAC” cut out of its surface. “MAC” refers to the Massachusetts Agricultural College, which was founded in Hampshire County in 1862 under the Land-Grant Colleges Act, and has evolved over the years into the University of Massachusetts Amherst. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, weathervanes mounted on agricultural buildings was a popular practice, although a more popular form of weathervanes were figural, usually reflecting the type of animal raised on that particular farm.

Sheep were a very popular weathervane shape! One major company to produce three-dimensional metal weathervanes, L.W. Cushing and Sons, was founded in Waltham, Massachusetts and operated between 1865-1933. Their 1883 catalog features multiple sheep, including rams and ewes for specific breeds. Weathervane use continues to be a popular pastime today, as a way for farmers to advertise what they raise. Can you spot any sheep weathervanes on farm buildings in Hampshire County today?

|

Treadmill In the mid nineteenth century, inventors thought of other ways to draw value from sheep. The Hadley Farm Museum’s collection contains a treadmill made in Bellows Falls, Vermont (patent 1884) that aimed to harness sheep power (or the power of other animals about the same size) to churn butter, run a clothes-washing machine, or otherwise power small machines. An example is preserved in the collections of the Hadley Farm Museum! |

Toy lamb, 1840, probably European. 1209.131. Old Sturbridge Village Collection. www.osv.org Toy lamb, 1840, probably European. 1209.131. Old Sturbridge Village Collection. www.osv.org

Old Sturbridge Village (Sturbridge): From Children’s Toys to Carding Machines

Children’s Toys This whimsical sheep toy in the collection of Old Sturbridge Village would have been an especially entertaining plaything for a child in the mid-nineteenth century. Made of real sheepskin and glass eyes, the sheep would have offered a soft, sensory experience for little hands to hold, and this particular toy also makes a sound! When the head is lowered or raised, the sheep toy bleats.7 The photograph of baby Joseph Lyman, held by his grandmother Hannah Moody in 1907, shows a similar toy lamb. |

Early nineteenth-century carding machine in operation at Old Sturbridge Village in Sturbridge, MA. www.osv.org

Early nineteenth-century carding machine in operation at Old Sturbridge Village in Sturbridge, MA. www.osv.org

Carding machines

In addition to raising sheep for their wool, Hampshire County residents ran carding mills, nineteenth- small water-powered mills that mechanized the process of combing woolen fibers into rolls that could then be spun. In a single season in 1803, Hampshire County residents learned that Roger Wing & Co had made a carding machine available in Williamsburg; Joel Norton & Co installed machines in both Westfield and Chesterfield; and Daves and Worthen had brought one to Wilbraham.8 In early 19th-century Hadley, Elizabeth Porter Phelps noted her husband's errands bringing wool home from carding mills in Amherst and Hadley.9 Women “soon discovered they could spin twice as much wool in a day by starting with the soft rolls produced by machine carding.”10 The advent of carding mills allowed Hampshire County households to increase the production of wool yarns by some 50%.11 By 1810, there were 57 carding machines and 67 fulling mills across Hampshire County (almost one third of Massachusetts’ total); those carding machines handled close to 260,000 pounds of wool (more than 30 percent more machines than the next largest producer, Worcester County, and handling almost 40 percent more wool).12

In addition to raising sheep for their wool, Hampshire County residents ran carding mills, nineteenth- small water-powered mills that mechanized the process of combing woolen fibers into rolls that could then be spun. In a single season in 1803, Hampshire County residents learned that Roger Wing & Co had made a carding machine available in Williamsburg; Joel Norton & Co installed machines in both Westfield and Chesterfield; and Daves and Worthen had brought one to Wilbraham.8 In early 19th-century Hadley, Elizabeth Porter Phelps noted her husband's errands bringing wool home from carding mills in Amherst and Hadley.9 Women “soon discovered they could spin twice as much wool in a day by starting with the soft rolls produced by machine carding.”10 The advent of carding mills allowed Hampshire County households to increase the production of wool yarns by some 50%.11 By 1810, there were 57 carding machines and 67 fulling mills across Hampshire County (almost one third of Massachusetts’ total); those carding machines handled close to 260,000 pounds of wool (more than 30 percent more machines than the next largest producer, Worcester County, and handling almost 40 percent more wool).12

Former stone remains of a sheep dip at the Rokeby Museum in Ferrisburgh, Vermont. (Photo: Rokeby Museum).

Former stone remains of a sheep dip at the Rokeby Museum in Ferrisburgh, Vermont. (Photo: Rokeby Museum).

Rokeby Museum (Ferrisburgh, Vermont)

Sheep dips

Evidence of sheep on the landscape can also incorporate natural resources, like sheep washes. Prior to shearing, many sheep were washed in the fleece to minimize the cleaning process after the sheep were shorn. To do this effectively, many sheep were driven through streams, rivers, or creeks or dipped into ponds so that their fleeces could be rinsed. A practice carried over from Europe, sheep washing was practiced into the nineteenth century and especially important for sheep flocks raised exclusively for their wool.13 Just north of Western Massachusetts, the stone remains of a “sheep dip” at the Rokeby Museum in Ferrisburgh, Vermont still survive along the bank of a former creek. During the Merino Craze, Vermont and Massachusetts farmers alike were intent upon increasing both wool production and wool quality, and clean fleeces were an important aspect of that cause. What bodies of water in Hampshire County can you picture filled with soggy sheep on a warm spring morning?

By the end of the nineteenth century, sheep dips had a different connotation. Increases in sheep infections caused by external parasites encouraged the invention of “sheep dip,” a powder whose main ingredient was arsenic that dissolved in water. Sheep were then submerged in the solution to kill any pests. Invented by William Cooper in England in 1852, Cooper’s Sheep Dip soon spread across to America in the nineteenth century for use by sheep farmers.14 The formula of sheep dip has changed considerably from its initial formula and is still in use today, infinitely safer for sheep and sheep farmers alike.

Sheep dips

Evidence of sheep on the landscape can also incorporate natural resources, like sheep washes. Prior to shearing, many sheep were washed in the fleece to minimize the cleaning process after the sheep were shorn. To do this effectively, many sheep were driven through streams, rivers, or creeks or dipped into ponds so that their fleeces could be rinsed. A practice carried over from Europe, sheep washing was practiced into the nineteenth century and especially important for sheep flocks raised exclusively for their wool.13 Just north of Western Massachusetts, the stone remains of a “sheep dip” at the Rokeby Museum in Ferrisburgh, Vermont still survive along the bank of a former creek. During the Merino Craze, Vermont and Massachusetts farmers alike were intent upon increasing both wool production and wool quality, and clean fleeces were an important aspect of that cause. What bodies of water in Hampshire County can you picture filled with soggy sheep on a warm spring morning?

By the end of the nineteenth century, sheep dips had a different connotation. Increases in sheep infections caused by external parasites encouraged the invention of “sheep dip,” a powder whose main ingredient was arsenic that dissolved in water. Sheep were then submerged in the solution to kill any pests. Invented by William Cooper in England in 1852, Cooper’s Sheep Dip soon spread across to America in the nineteenth century for use by sheep farmers.14 The formula of sheep dip has changed considerably from its initial formula and is still in use today, infinitely safer for sheep and sheep farmers alike.

needlework picture: young man and woman. Mary Upeble, needlework of wool and silk embroidery, 1767. HD 1734. Historic Deerfield Collection.

needlework picture: young man and woman. Mary Upeble, needlework of wool and silk embroidery, 1767. HD 1734. Historic Deerfield Collection.

Historic Deerfield (Deerfield, MA)

Needlework Embroidery

Often associated with the pastoral or the biblical (as seen in the sheep gravestones mentioned earlier), sheep imagery can also be found in a variety of forms of visual culture, from landscape paintings to needlework embroidery. This piece of needlework, in the collection of Historic Deerfield, was completed by Mary Upeble of Newburyport, Massachusetts in 1767. The stitched scene features, in addition to the couple in the center and floral motifs, a ewe and lamb chased by a dog at the base of a hillside. The work, completed in cross and diagonal tent stitches, was made with silk and wool threads.15 Sheep were a popular needlework motif, and their popularity continues today in colorwork knitting patterns, needlework, and needle felting.

Needlework Embroidery

Often associated with the pastoral or the biblical (as seen in the sheep gravestones mentioned earlier), sheep imagery can also be found in a variety of forms of visual culture, from landscape paintings to needlework embroidery. This piece of needlework, in the collection of Historic Deerfield, was completed by Mary Upeble of Newburyport, Massachusetts in 1767. The stitched scene features, in addition to the couple in the center and floral motifs, a ewe and lamb chased by a dog at the base of a hillside. The work, completed in cross and diagonal tent stitches, was made with silk and wool threads.15 Sheep were a popular needlework motif, and their popularity continues today in colorwork knitting patterns, needlework, and needle felting.

1 Nancy M. Guyton, “Domestic production of cloth in the town of Hadley, 1760-1800” (unpublished seminar paper, Historic Deerfield, 1981), study based on evidence from 31 probate inventories and Massachusetts tax valuation lists for 1771, 1781 and 1786, p. 9.

2 See Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, “Wheels, Looms, and the Gender Division of Labor in Eighteenth-Century New England,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 55, No. 1 (Jan., 1998), pp. 3-38; and Carole Shammas, “How Self-Sufficient Was Early America?,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Autumn, 1982), pp. 247-272.

3 Adrienne d. Hood, The Weaver’s Craft: Cloth, Commerce, and Industry in Early Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 72. This paragraph is drawn from Miller, Entangled Lives.

4 Theodore Gregson Huntington, sketches, 63, Box 21 folder 4, PPHFP, UMass SCUA. See also Marion Channing, The Textile Tools of Colonial Homes (Marion, Massachusetts, 1971), 16-26, as cited in Earle, Home Life in Colonial Days (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1898), 174, 196-200.

5 Theodore Gregson Huntington, sketches, 63, Box 21 folder 4, PPHFP, UMass SCUA.

6 Hand sheep shears made in Sheffield, England, 1950-1955 2021, Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences, accessed 16 September 2022, https://ma.as/232583

7 https://collections.osv.org/object-1-209-131

8 Hampshire Gazette, June 6 and 15, 1803, and (Springfield) Federal Spy, June 6 and August 23, 18039 Elizabeth Porter Phelps, memorandum book, e.g. 4 November 1804, and 6 August 1809, UMass SCUA.

10 Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of the American Myth (Vintage Books, 2001), 289.

11 Clark, Roots of Rural Capitalism, 140, citing Jeremy, Transatlantic Industrial Revolution: The Diffusion of Textile Technologies between Britain and America, 1790-1830s (Oxford, 1981), 126.

12 Clark, Roots of Rural Capitalism, 94, 103.

13 Edward Norris Wentworth, America’s Sheep Trails (Ames: Iowa State College Press, 1948).

14 Andrew Clayman. “William Cooper & Nephews Inc., est 1852.” Made in Chicago Museum. https://www.madeinchicagomuseum.com/single-post/william-cooper-and-nephews/

15 https://museums.fivecolleges.edu/detail.php?t=objects&type=ext&id_number=HD+1734

2 See Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, “Wheels, Looms, and the Gender Division of Labor in Eighteenth-Century New England,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 55, No. 1 (Jan., 1998), pp. 3-38; and Carole Shammas, “How Self-Sufficient Was Early America?,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Autumn, 1982), pp. 247-272.

3 Adrienne d. Hood, The Weaver’s Craft: Cloth, Commerce, and Industry in Early Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 72. This paragraph is drawn from Miller, Entangled Lives.

4 Theodore Gregson Huntington, sketches, 63, Box 21 folder 4, PPHFP, UMass SCUA. See also Marion Channing, The Textile Tools of Colonial Homes (Marion, Massachusetts, 1971), 16-26, as cited in Earle, Home Life in Colonial Days (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1898), 174, 196-200.

5 Theodore Gregson Huntington, sketches, 63, Box 21 folder 4, PPHFP, UMass SCUA.

6 Hand sheep shears made in Sheffield, England, 1950-1955 2021, Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences, accessed 16 September 2022, https://ma.as/232583

7 https://collections.osv.org/object-1-209-131

8 Hampshire Gazette, June 6 and 15, 1803, and (Springfield) Federal Spy, June 6 and August 23, 18039 Elizabeth Porter Phelps, memorandum book, e.g. 4 November 1804, and 6 August 1809, UMass SCUA.

10 Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of the American Myth (Vintage Books, 2001), 289.

11 Clark, Roots of Rural Capitalism, 140, citing Jeremy, Transatlantic Industrial Revolution: The Diffusion of Textile Technologies between Britain and America, 1790-1830s (Oxford, 1981), 126.

12 Clark, Roots of Rural Capitalism, 94, 103.

13 Edward Norris Wentworth, America’s Sheep Trails (Ames: Iowa State College Press, 1948).

14 Andrew Clayman. “William Cooper & Nephews Inc., est 1852.” Made in Chicago Museum. https://www.madeinchicagomuseum.com/single-post/william-cooper-and-nephews/

15 https://museums.fivecolleges.edu/detail.php?t=objects&type=ext&id_number=HD+1734

Proudly powered by Weebly