Forty Acres and Phelps Farm: One Farm's Story

By: Marla Miller and Emily Whitted

Department of History, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

“The ancestral home of the Phelps family,” Clifton Johnson Collection, Jones Library (Amherst) Special Collections.

“The ancestral home of the Phelps family,” Clifton Johnson Collection, Jones Library (Amherst) Special Collections.

Many people who have an interest in the history of sheep cultivation may know about the New England “Merino sheep craze” and its strong connection to the state of Vermont. What’s less well known is the fact that the craze actually started in Massachusetts, and that Phelps Farm in Hadley, Massachusetts, was one of the first adopters of the breed. In fact, this family–an unusually affluent and influential family whose history is today preserved and shared through the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Museum–has a long history with sheep farming that offers a microcosm of the industry’s history in Hampshire County writ large.

Charles P. Phelps and the introduction of Merino Sheep to Hadley

Even before the nineteenth century American farmers were already seeking to introduce Merinos to the country, attracted to their quality wool and mutton. In 1802, one man wrote to the Massachusetts Society for Promoting Agriculture that he was "convinced that this race of sheep, of which I believe not one has been brought to the U.S. . . might be introduced with great benefit to our country."1 The only problem was that Spain had strictly controlled their population of Merino sheep and did not export them.

This meant the only way to import them into the United States was to smuggle them. It wasn’t until after the turn of the nineteenth century that the United States saw a dramatic rise in the importation of Merino sheep. Surprisingly enough, a direct connection can be drawn between Napoleon's invasion of Spain in 1808 and the increase of Merino sheep as he took the sheep from Spain and sold them, making it far easier for countries outside of the country to breed and import them. Records show that as early as 1809 thousands of Merinos were imported into the country.

Even before the nineteenth century American farmers were already seeking to introduce Merinos to the country, attracted to their quality wool and mutton. In 1802, one man wrote to the Massachusetts Society for Promoting Agriculture that he was "convinced that this race of sheep, of which I believe not one has been brought to the U.S. . . might be introduced with great benefit to our country."1 The only problem was that Spain had strictly controlled their population of Merino sheep and did not export them.

This meant the only way to import them into the United States was to smuggle them. It wasn’t until after the turn of the nineteenth century that the United States saw a dramatic rise in the importation of Merino sheep. Surprisingly enough, a direct connection can be drawn between Napoleon's invasion of Spain in 1808 and the increase of Merino sheep as he took the sheep from Spain and sold them, making it far easier for countries outside of the country to breed and import them. Records show that as early as 1809 thousands of Merinos were imported into the country.

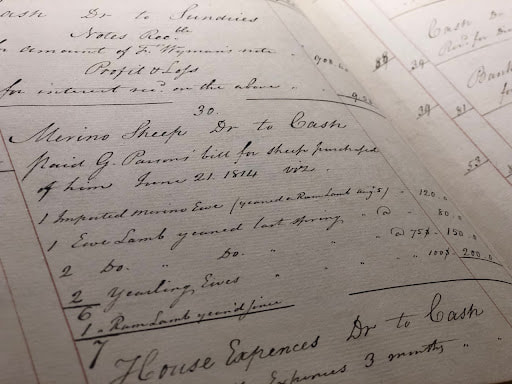

Forty Acres was one of the first local farms to receive Merino sheep. Charles Phelps Jr., an early member of the Massachusetts Society for Promoting Agriculture, purchased a “full blood merino ewe imported from Spain” from Gorham Parsons in May 1814. The diary of Elizabeth Porter Phelps (the wife of Charles Phelps, Jr and mother of Charles P. Phelps), mentions this event:“May 1, 1814: Monday morn Charles set off with a wagon for Merino sheep for my husband and son.” On July 3rd she noted “my son (Charles Phelps) went to Williamsburgh with our and his Merino wool;” apparently, only two months after the sheep arrived, the family was already sending the wool to be processed and sold.

Of course, these Merinos were not the first sheep to be kept on the farm; in fact, sheep had been part of the farmstead since the beginning. In 1752, when the house at Forty Acres was first built by Moses and Elizabeth Porter, Charles P. Phelps’ grandparents, the Porters created an area for sheep to graze just east of the main house. Though the number of sheep in this period was relatively small (just two were present in the late 1750s), it did show an early interest in raising sheep on the farm.

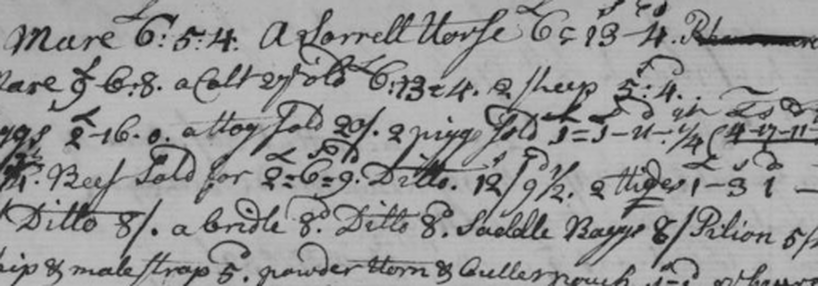

Detail, Moses Porter probate inventory, Hampshire County Registry of Probate, 1757.

The 1757 inventory of Moses Porter’s estate lists two sheep among the farm’s larger population of cattle, horses, and pigs. The inventory also lists sheep shears, sheep skins, a wool wheel, and other evidence of sheep and wool production.

Moses and Elizabeth’s daughter, Elizabeth, married Charles Phelps, Jr. in 1770. Charles and Elizabeth Porter Phelps greatly expanded the farm's production of wool and mutton. In 1777, Phelps Jr. recorded having 48 sheep, which were housed in a sheep house near a pasture on Mount Warner.2 Structures added to the farmstead between 1785 and 1807 included a large barn for the farm’s cattle as well as another sheephouse.3 Seasonally, they hired extra hands to shear wool fleeces and to process the sheep for meat as well as well.

In August 1815, the center of gravity for sheep cultivation moved across the street, to a site that would become Phelps Farm, the home of Charles and Elizabeth’s son Charles P. Phelps. A member of the family’s third generation, he “had the old cider house and the sheep house moved over to his lot where the barn is”--work that required twenty-eight yoke of oxen and “near double that number of hands.”4 Accounts from these years show payments to a local man named William Powell for the annual June shearings; these entries also give a sense of the size of the flock: about a dozen sheep were present in 1806 and 1807, and about two dozen by 1814. The farm also charged neighboring farms for pasturing their sheep together with the Phelps’ flock–which allowed farmers with too small a number of sheep to warrant fenced fields and other necessary features of sheep cultivation to nonetheless keep some sheep for wool and meat.5

By these years, children of the family–now the fourth generation of residents–were spinning wool from the farm’s sheep. Writing about her granddaughters, Elizabeth Porter Phelps wrote with pride that little Elizabeth, just nine-and-a-half years old, “has spun near 2 run last Satt.” But apparently so much spinning could be hard on the little girl’s hands: one Sunday the child’s “forefinger on her left hand begun to have a sore come upon it like Martha’s, and it was been increasing ever since, & I think it not likely she can spin some time.” Elizabeth’s injury proved “a good chance” for seven-year-old Bethia, who had “been very busy trying her possibles.” Little Bethia “has worked out her own way pretty much nearly half a run I guess in all, but,” Phelps observed, “she inclines to spin too coarse.” Nevertheless, Bethia wanted her grandmother to be sure and tell her mother, “I have learned to spin.” Sister Elizabeth, on the other hand, the proud grandmother could report, “spins pretty yarn.”6

Entry receiving Merino sheep, Waste Book A, Phelps and Rand Collection, Baker Library, Harvard University.

Entry receiving Merino sheep, Waste Book A, Phelps and Rand Collection, Baker Library, Harvard University.

It was about this time that Charles P. Phelps (the uncle of these new spinners) developed his vision for bringing merino sheep to Hadley. In the same year his parents received their ewe, Charles P. Phelps received an undisclosed number of Merinos as well. In March 1814, Charles P. Phelps purchased a copy of Tessier’s Complete Treatise on Merinos and Other Sheep. The book contains a description of a recommended sheep house, and so hints at the structure that might have been present at Phelps Farm; the height, Tessier wrote, should be 12 feet or more, allowing 8 square feet per ram, wether, or ewe, and 6 per lamb (which, given the size of Phelps’ flock at this time, would have required a building of around 290 square feet).7 Phelps’ accounts tell us that a man named John Wood, who was also the man hired for his expertise in shearing that year (25 sheep) was paid for five days’ work hewing and framing a sheep house; he spent twelve more days on the construction of it, assisted by another local man, Reuban Potter.8

Later Charles P. Phelps would become the vice president of the Hampshire, Franklin and Hampden Agricultural Society—a local version of the MSPA to which his father had belonged.9 Sadly, though an early adopter of the Merino craze, Phelps in time felt as if the investment was a failure. In his account book he refers to “10 merino sheep, nearly a total loss,” going on to explain that he believed that he threw away $1000 buying the Merinos.10 In fact, on August 25, 1818 he put an advertisement selling a “small flock of Merino Sheep consisting of 29 Ewes, 2 Bucks, and 5 Wethers—warranted of pure blood” in the Hampshire Gazette.11 On November 6, 1819, Phelps sold “40 merino sheep to Isaac C. Bates for $5 each, $200; also 18 sheep to Mr Hill, for $2, total $36.” 12

Though Phelps lost interest in the Merino fad, the farm continued to raise sheep; they made use of the wool and meat, and sold sheep to local farms. In the summer of 1819, for instance, hey sold 157 pounds of wool to Shepard and Jones, a local manufactory.13 Toward the end of his life, Theodore Gregson Huntington put down his boyhood memories of life on the farm, including the shearing of the family’s sheep in these years. He recalled fleece in its “entire” being in once piece “carefully rolled up and tied together to be sent to the carding mill or sold”--evidence that the family had begun to make sure of the carding mills that had cropped up by this time (see the essay here on sheep cultivation in the 19th century).14

Records from this period also tell us that sheep were raised in the community’s small community of farmers of color, including Joshua Boston, an African American farmer in Hadley. Boston had, as a young man, been enslaved by the Porter family in Hadley. He became free in the third quarter of the eighteenth century, and by the early nineteenth century was a farmer who had his own household near the north end of Hadley village, though he also performed farmwork for area families.15 As late as 1817 and 1818, Boston appears in farm accounts kept by Charles P. Hitchcock, then the manager of Charles P. Phelps’ farm, purchasing sheep alongside rye, cheese, fish and other products, expenses offset by his labor “carting dirt,” dressing flax, and other farm chores.16

The 1850 agricultural census shows that there were no longer any sheep at Phelps Farm; the family had given up on the endeavor entirely. Census returns through the 1880s confirms that there were no longer sheep present, either at Phelps Farm or Forty Acres.17 By the 1870s, the early nineteenth-century sheep house built in excited anticipation of Charles P. Phelps’ merino sheep flock was being used for vegetable storage.18

In the twentieth century, however, sheep would make a comeback at Phelps Farm. In 1893, Frederic Dan Huntington, a descendant who had come to own and use Forty Acres as a summer home and hobby farm, acquired Phelps Farm across the street as a summer property for his daughter Ruth. She would go on to launch a sizeable local dairy operation there that became the farm’s focus, and in 1925, she convinced her son, John Archibald (John A.) Sessions to join her there.19 Sessions had attended Harvard, graduating from the college in 1921; he and Ruth together, as well as his wife Doheney Sessions, would lead the Hadley farm for many years, and though the focus was on supplying a dairy route that served residents of Northampton and Hadley, sheep returned to Phelps Farm in these years, though in modest numbers. Sheep cultivation had migrated to other parts of Massachusetts in these years; fewer than 1000 sheep grazed Hampshire County about this time.20

Later Charles P. Phelps would become the vice president of the Hampshire, Franklin and Hampden Agricultural Society—a local version of the MSPA to which his father had belonged.9 Sadly, though an early adopter of the Merino craze, Phelps in time felt as if the investment was a failure. In his account book he refers to “10 merino sheep, nearly a total loss,” going on to explain that he believed that he threw away $1000 buying the Merinos.10 In fact, on August 25, 1818 he put an advertisement selling a “small flock of Merino Sheep consisting of 29 Ewes, 2 Bucks, and 5 Wethers—warranted of pure blood” in the Hampshire Gazette.11 On November 6, 1819, Phelps sold “40 merino sheep to Isaac C. Bates for $5 each, $200; also 18 sheep to Mr Hill, for $2, total $36.” 12

Though Phelps lost interest in the Merino fad, the farm continued to raise sheep; they made use of the wool and meat, and sold sheep to local farms. In the summer of 1819, for instance, hey sold 157 pounds of wool to Shepard and Jones, a local manufactory.13 Toward the end of his life, Theodore Gregson Huntington put down his boyhood memories of life on the farm, including the shearing of the family’s sheep in these years. He recalled fleece in its “entire” being in once piece “carefully rolled up and tied together to be sent to the carding mill or sold”--evidence that the family had begun to make sure of the carding mills that had cropped up by this time (see the essay here on sheep cultivation in the 19th century).14

Records from this period also tell us that sheep were raised in the community’s small community of farmers of color, including Joshua Boston, an African American farmer in Hadley. Boston had, as a young man, been enslaved by the Porter family in Hadley. He became free in the third quarter of the eighteenth century, and by the early nineteenth century was a farmer who had his own household near the north end of Hadley village, though he also performed farmwork for area families.15 As late as 1817 and 1818, Boston appears in farm accounts kept by Charles P. Hitchcock, then the manager of Charles P. Phelps’ farm, purchasing sheep alongside rye, cheese, fish and other products, expenses offset by his labor “carting dirt,” dressing flax, and other farm chores.16

The 1850 agricultural census shows that there were no longer any sheep at Phelps Farm; the family had given up on the endeavor entirely. Census returns through the 1880s confirms that there were no longer sheep present, either at Phelps Farm or Forty Acres.17 By the 1870s, the early nineteenth-century sheep house built in excited anticipation of Charles P. Phelps’ merino sheep flock was being used for vegetable storage.18

In the twentieth century, however, sheep would make a comeback at Phelps Farm. In 1893, Frederic Dan Huntington, a descendant who had come to own and use Forty Acres as a summer home and hobby farm, acquired Phelps Farm across the street as a summer property for his daughter Ruth. She would go on to launch a sizeable local dairy operation there that became the farm’s focus, and in 1925, she convinced her son, John Archibald (John A.) Sessions to join her there.19 Sessions had attended Harvard, graduating from the college in 1921; he and Ruth together, as well as his wife Doheney Sessions, would lead the Hadley farm for many years, and though the focus was on supplying a dairy route that served residents of Northampton and Hadley, sheep returned to Phelps Farm in these years, though in modest numbers. Sheep cultivation had migrated to other parts of Massachusetts in these years; fewer than 1000 sheep grazed Hampshire County about this time.20

John A. Sessions with sheep at Phelps Farm, Charles (Moses) Porter Phelps Farm Collection, UMass SCUA, Unprocessed papers.

John A. Sessions with sheep at Phelps Farm, Charles (Moses) Porter Phelps Farm Collection, UMass SCUA, Unprocessed papers.

The dairy operation at Phelps Farm lasted until the late 1970s, but after the dairy herd was sold, the land and buildings began to be used on a rental basis by Parsons Farms, which among other things has long carried on a large sheep farming enterprise in Hadley. In the last quarter of the twentieth century, up to 100 sheep grazed land at Phelps Farm.’

Sheep, then, were part of the history and landscape of Forty Acres and Phelps Farm for some 250 years, from the middle of the eighteenth century when the Porters moved to this land to the late twentieth century, when the Parsons family continued to graze sheep there. The farm saw the peak of Merino mania, as well as many other moments in the ebb and flow of sheep cultivation in Hampshire County.

Sheep, then, were part of the history and landscape of Forty Acres and Phelps Farm for some 250 years, from the middle of the eighteenth century when the Porters moved to this land to the late twentieth century, when the Parsons family continued to graze sheep there. The farm saw the peak of Merino mania, as well as many other moments in the ebb and flow of sheep cultivation in Hampshire County.

1 B.J. Belanus, B. J. They Lit Their Cigars with Five Dollar Bills: The History of the Merino Sheep Industry in Addison County. National Endowment for the Humanities, 1977.

2 See the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers (hereafter PPHFP), UMass SCUA, Box 4 folder 16.

3 Margaret Mary Fitzpatrick, Forty Acres: A New England Homestead and Its Owners, 1752-1814 (MA Thesis, Univ. of Delaware, June 1976) 18.

4 Elizabeth Porter Phelps, diary, August 13 and October 2, 1815, PPHFP, UMass SCUA, Box 7 folder4. The sheep house was moved by Elijah Nash, who earned $4.50 for three days of work. See Charles Porter Phelps, Farm Accounts, 1818-1841 (A), December 2, 1818, p. 16, Phelps and Rand Records, Baker Library, Harvard University.

5 Waste Book A (1803-1816), Phelps and Rand Records, Baker Library, Harvard University.

6 Elizabeth Porter Phelps to Elizabeth Whiting Phelps Huntington, December 14, 1812, PPHFP, UMass SCUA, Box 5 folder 11. The following month, when the girls were visiting the Huntington grandparents in Connecticut, Dan wrote Elizabeth, wanting to know if they were homesick, and also “how much you have spun—how much you spin in a day, how much Bethia has spun.” See Dan Huntington to Elizabeth and Bethia Huntington, January 7, 1813, PPHFP, UMass SCUA, Box 15 folder 7,

7 Charles P. Phelps, Farm Memoranda and Expenses, March 14, 1814, Charles (Moses) Porter Phelps Farm Collection, Unprocessed materials, UMass SCUA; Tessier, Complete Treatise on Merinos and Other Sheep, 52-53.

8 Waste Book A (Vol II, 1803-1816), Phelps and Rand Reocrds, Baker Library, Harvard University.

9 Hampshire, Franklin, and Hampden Agricultural Society 1820 report, Charles P. Phelps, PPHFP, UMASS SCUA, Box 16:15.

10 Charles Porter Phelps, Autobiography [handwritten copy], 106, 107, PPHFP, UMASS SCUA, Box 16:15.

11 Hampshire Gazette, August 25, 1818.

12 Charles Porter Phelps, Farm Accounts, 1818-1841 (A), p. 16, Baker Library, Harvard University.

13 Charles Porter Phelps, Farm Accounts, 1818-1841 (A), p. 20, Charles (Moses) Porter Phelps Farm Collection, UMass SCUA, Unprocessed papers.

14 Theodore Gregson Huntington, “Sketches…of Family Life in Hadley” (1882), 46, PPHFP, UMASS SCUA, Box 21:5.

15 For more on Boston, see Marla Miller, “Joshua Boston,” on the website “Documenting Black Lives in the Early Connecticut Valley.

16 Charles P. Hitchcock ledger, (Moses) Charles Porter Phelps Farm Collection, Unprocessed materials, UMass SCUA.

17 Agricultural Census (U.S., Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules), 1850-1880.

18 See Regina S. Leonard, “The Porter-Phelps-Huntington Property, 1659-1955: History of the Vernacular Landscape in Context” (MA Thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2000), 61. On the sheep house move in 1818, see December 31, 1818. On the 1836 repair, see September 1836 entries in Phelps Ledger Vol 3, Baker Library, Harvard University. On the structure being in use at least as late as the 1870s for vegetable storage, see Charles Phelps IV journals, Charles (Moses) Porter Phelps Farm Collection, UMass SCUA, Unprocessed papers, passim.

19 See Hampshire County Registry of Deeds, Book 818, p. 500

20 Some 984 sheep were counted in Hampshire County in 1919, compared to just over 1000 in Hampden, while over 4000 sheep were found in Franklin County, and nearly 3000 in Berkshire; see the 1920 Census: Volume 6. Agriculture, Reports for States, with Statistics for Counties and a Summary for the United States and the North, South, and West, p. 162.

2 See the Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers (hereafter PPHFP), UMass SCUA, Box 4 folder 16.

3 Margaret Mary Fitzpatrick, Forty Acres: A New England Homestead and Its Owners, 1752-1814 (MA Thesis, Univ. of Delaware, June 1976) 18.

4 Elizabeth Porter Phelps, diary, August 13 and October 2, 1815, PPHFP, UMass SCUA, Box 7 folder4. The sheep house was moved by Elijah Nash, who earned $4.50 for three days of work. See Charles Porter Phelps, Farm Accounts, 1818-1841 (A), December 2, 1818, p. 16, Phelps and Rand Records, Baker Library, Harvard University.

5 Waste Book A (1803-1816), Phelps and Rand Records, Baker Library, Harvard University.

6 Elizabeth Porter Phelps to Elizabeth Whiting Phelps Huntington, December 14, 1812, PPHFP, UMass SCUA, Box 5 folder 11. The following month, when the girls were visiting the Huntington grandparents in Connecticut, Dan wrote Elizabeth, wanting to know if they were homesick, and also “how much you have spun—how much you spin in a day, how much Bethia has spun.” See Dan Huntington to Elizabeth and Bethia Huntington, January 7, 1813, PPHFP, UMass SCUA, Box 15 folder 7,

7 Charles P. Phelps, Farm Memoranda and Expenses, March 14, 1814, Charles (Moses) Porter Phelps Farm Collection, Unprocessed materials, UMass SCUA; Tessier, Complete Treatise on Merinos and Other Sheep, 52-53.

8 Waste Book A (Vol II, 1803-1816), Phelps and Rand Reocrds, Baker Library, Harvard University.

9 Hampshire, Franklin, and Hampden Agricultural Society 1820 report, Charles P. Phelps, PPHFP, UMASS SCUA, Box 16:15.

10 Charles Porter Phelps, Autobiography [handwritten copy], 106, 107, PPHFP, UMASS SCUA, Box 16:15.

11 Hampshire Gazette, August 25, 1818.

12 Charles Porter Phelps, Farm Accounts, 1818-1841 (A), p. 16, Baker Library, Harvard University.

13 Charles Porter Phelps, Farm Accounts, 1818-1841 (A), p. 20, Charles (Moses) Porter Phelps Farm Collection, UMass SCUA, Unprocessed papers.

14 Theodore Gregson Huntington, “Sketches…of Family Life in Hadley” (1882), 46, PPHFP, UMASS SCUA, Box 21:5.

15 For more on Boston, see Marla Miller, “Joshua Boston,” on the website “Documenting Black Lives in the Early Connecticut Valley.

16 Charles P. Hitchcock ledger, (Moses) Charles Porter Phelps Farm Collection, Unprocessed materials, UMass SCUA.

17 Agricultural Census (U.S., Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules), 1850-1880.

18 See Regina S. Leonard, “The Porter-Phelps-Huntington Property, 1659-1955: History of the Vernacular Landscape in Context” (MA Thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2000), 61. On the sheep house move in 1818, see December 31, 1818. On the 1836 repair, see September 1836 entries in Phelps Ledger Vol 3, Baker Library, Harvard University. On the structure being in use at least as late as the 1870s for vegetable storage, see Charles Phelps IV journals, Charles (Moses) Porter Phelps Farm Collection, UMass SCUA, Unprocessed papers, passim.

19 See Hampshire County Registry of Deeds, Book 818, p. 500

20 Some 984 sheep were counted in Hampshire County in 1919, compared to just over 1000 in Hampden, while over 4000 sheep were found in Franklin County, and nearly 3000 in Berkshire; see the 1920 Census: Volume 6. Agriculture, Reports for States, with Statistics for Counties and a Summary for the United States and the North, South, and West, p. 162.